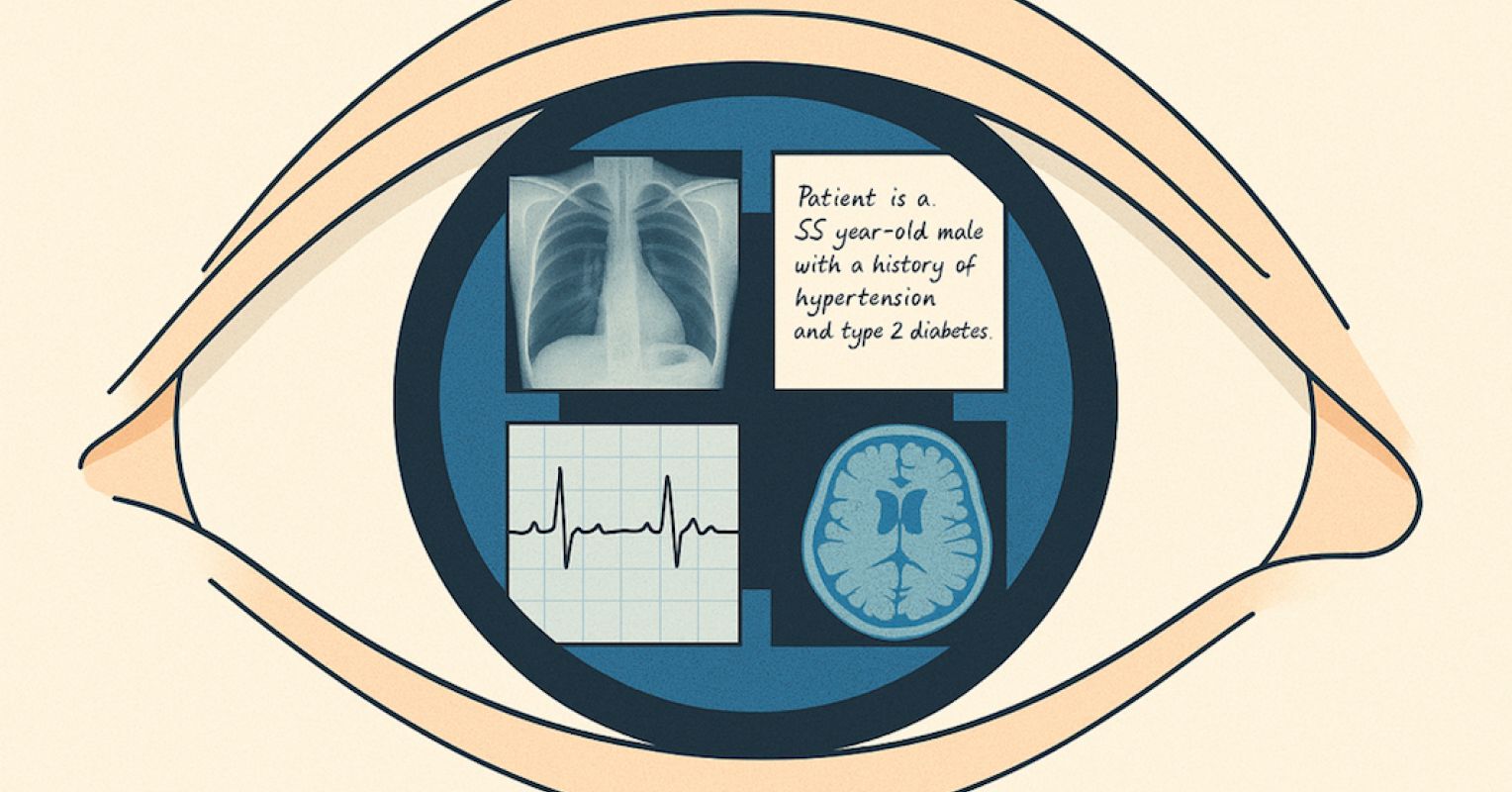

The simple truth is that medicine is always multimodal. And a physician’s mind doesn’t travel in a straight line. It drifts from the patient’s story to the computed tomography (CT) image, to the lab values on a screen, and back to the clues in a physical exam. Diagnosis is rarely the product of one kind of evidence and is most commonly the synthesis of many that are layered together into something coherent enough to act on.

Until now, most artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine has lived in a narrower frame: Text in, text out. Useful for summarizing notes, recalling guidelines, or answering exam-style questions. But it’s far from the layered integration that clinicians rely on.

The Study That Changes the Frame

A new study from Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute may be “eye-opening” in shifting that perception. In controlled evaluations, GPT-5 (OpenAI’s latest model) was given complex cases that combined patient histories, lab results, and medical images. These weren’t simplified scenarios and came from rigorous benchmarks like the MedXpertQA dataset, designed to reflect the complexity of actual clinical reasoning.

GPT-5 outperformed “pre-licensed human experts” by more than 24 percent in multimodal reasoning and nearly 30 percent in multimodal understanding. In one case, it identified an esophageal perforation by synthesizing CT findings, lab values, and key physical signs and then recommended the correct next step in management.

It’s important to note that these participants were advanced medical trainees who had completed most of their formal education but were not yet fully licensed. (The paper is unclear whether these subjects were just out of medical school or had completed a residency.) Nevertheless, this group offers a fair, standardized benchmark for structured test cases. But it’s not the same as testing seasoned, fully licensed specialists in the clinic.

A Leap or Another Step?

For clinicians, trust in AI will not be built on its ability to ace multiple-choice questions in isolation. It will come from seeing an AI engage with the actual scans, the real lab sheets, the messy clinical notes.

When AI looks at the same image a clinician does and draws on a multimodal narrative, its reasoning may be less like a detached algorithm and may become more contextual. And the shift from outsider to more of a cognitive participant may be at the heart of professional acceptance.

Regulators Notice the Difference

It’s also worth noting that in general, regulatory bodies tend to favor systems that fit into existing clinical workflows rather than those that require changing practice to accommodate the tool. Multimodal capability makes that possible. A CT remains a CT, a lab report remains a lab report, but the AI just sees them all together. This alignment with familiar processes may accelerate approval for real-world deployment.

From Benchmarks to Bedside

Of course, dominance in benchmarks is not the same as success at the bedside. Patients arrive with incomplete histories, contradictory findings, and symptoms that don’t fit textbook patterns. The Emory researchers emphasize that these results come from idealized, standardized testing conditions. And here’s how they captured this concern in their own words:

However, it is important to note that the benchmarks used reflect idealized testing conditions and may not fully capture the variability, uncertainty, and ethical considerations of real-world practice.

Real-world validation will require more work that includes prospective trials, careful calibration, and a willingness to examine where the AI fails. But I think the signal is strong, and once an AI starts seeing through multiple lenses at once, it begins to operate in a similar “cognitive space” as a clinician.

The AI Will See You Now

When AI stops merely reading about a patient and starts “seeing” them through images, labs, and narratives, it moves from a fractured perspective to a more consolidated clinical decision-making process. Multimodal understanding may be the bridge that shifts AI from an interesting adjunct to a trusted participant in care. And in a curious way, it may allow technology to see beyond the physical or computational skills of even the best clinician to offer not just adjunctive but expanded insights into care.

In medicine, we’ve always valued that second opinion or second set of eyes. AI’s performance suggests those eyes may soon be digital and might be sharper than we expected.